There are few people I’ve met who found the experience of dealing with shared libraries pleasant. Personally, I really despise them. The whole idea of “shared code” is great and all, but the implementations in the Unix and Windows worlds are not something I would like to deal with. I would like to go as far as saying, “shared libraries suck”, but that would mean a lot of people are going to flame me - just because they are extremely prevalent and that they’re “working” for a vast majority of cases.

Before I proceed with the post, I would like to share two quotes from people that I greatly respect:

the trouble with shared libraries is that they seem at first quite reasonable, and indeed at a fairly abstract level, it seems irrational to be more opposed to them than any other form of sharing, such as shared text, but the mechanics of linking and sharing (especially on current processors), and of configuration control, have so many hard facts that the simplicity of the original is quite lost. having experienced several variants, i find it now saves time just to adopt the irrational position from the start.

i think i’d rather have (say) mondrian memory protection than either shared libraries or the vm crud they keep adding to chips and systems.

-Charles Forsyth

and,

shared libraries are obviously a good idea until you’ve actually used them. then whether it’s obvious or not that they’re a bad idea is mostly a matter of how close you are to trying to get them to work.

-Rob Pike

I like static linking. But code these days is getting extremely complex and bloated, so people needed an alternative. Instead of focusing on making their code more cleaner and lean, they started thinking about they can share this huge piece of complex and bloated code across several applications. If you think about it, if your code is small and clean, you wouldn’t feel the need for shared libraries.

Ulrich Drepper’s famous page on why static linking is considered harmful is worth a mention here. In point 1, he says “fixes have to be applied to only place”, but that also means that it takes only one “fix” to introduce two bugs that has wide-reaching consequences (imagine a “fix” that introduces two new bugs in a shared libc - this has happened!). The other points are probably valid, but his conclusion is certainly not:

The often used argument about statically linked apps being more portable (i.e., can be copied to other systems and simply used since there are no dependencies) is not true since every non trivial program needs dynamic linking at least for one of the reasons mentioned above.

There exists an entirely functional, portable, (and superior) operating system that doesn’t support shared libraries (and for very good reasons).

If you’re not convinced that shared libraries are clunky hacks that shouldn’t be used, that’s Ok. Let’s assume that shared libraries are a great idea and are a boon to computing. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t look at better ways of achieving the same goals in a cleaner, better manner.

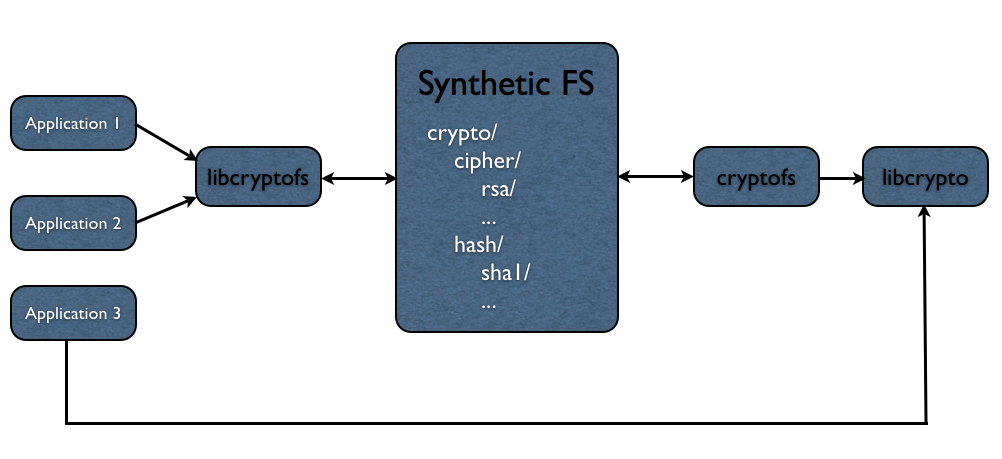

As an advocate of the Plan 9 operating system and it’s underlying principles, my opinion may be a bit biased; but I think synthetic file systems are frickin’ awesome. If I were to design a system where several applications were to share common cryptography code (for example), here’s how I would do it:

The synthetic file system in the center works something like this: applications wanting some cryptography work to be done read and write to files exposed by the FS. For example, Application 1 would write the data it needs SHA-1ed to /crypto/hash/sha1/data, and a subsequent read on the same file would return the hash (the read would block until the SHA1 was actually calculated). The great thing about such filesystems are that they are language independent, since almost any respectable language has file operations in its standard library.

However, in order to take care of things like type safety, we make this very tiny, stub library called libcryptofs. The job of this library is merely to pass on data from applications to files, while ensuring the compiler catches type safety errors (because this library is statically linked to every application wanting to use CryptoFS) and also performing the task of gracefully handling errors like /crypto being absent.

On the other side of the FS, we have cryptofs, the code that is responsible for actually providing the filesystem. It would statically link with a synthetic filesystem library (Not show in diagram: lib9p on Plan 9, maybe FUSE on Linux - but would you statically link with it? lib9p is also available on POSIX systems, by the way, thanks to the Plan 9 from User Space project). But this library is also small, because it delegates the actual cryptography operations to libcrypto, the library that has all the code implementing SHA1, RSA and so on.

But since libcrypto is a small and awesomely written cryptography library, Application 3 may decide to directly link with it. Suitable for embedded devices or other memory-starved environments, where you want to avoid the whole FS in the middle because you know there is only going to be one application needing it.

Now, what about versioning? That is, after all, why shared libraries began to suck. With filesystems, it’s trivial to add functionality without breaking applications depending on older versions of your FS. That’s because all the compiler sees is a bunch of fopen/fread/fwrites and is not going to complain if the version of the filesystem changes because it doesn’t know. Alternatively, if you’re thinking of modifying the behavior of your filesystem; consider providing a version file in the root of your FS right from the beginning. Applications would then write the version number they expect to be working with in that file as a way of initializing the filesystem - and multiple versions of the filesystem can live in harmony if your system implements per-process namespaces (Plan 9 has them, Linux does too thanks to CLONE_NEWNS) because every application “sees” its own private copy of the CryptoFS file hierarchy.

In summary, the answer is to write lean, efficient and small pieces of code (a very difficult task if you’re thinking of using the GNU toolchain!) and use filesystems in place of shared libraries. Plan 9 has been using it successfully for years, and I think we should learn something and try to apply the philosophy to other systems we love as well: Firefox extensions, COM models for Games, Plugin systems; anywhere we make extensive used of shared libraries and dynamic loading. Let me know what you think, and whether you would consider this approach for your next project! I know I certainly will.